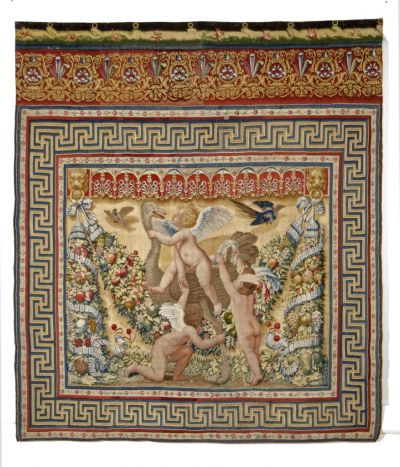

Tapestry - so called Medici tapestry - Playing putti I (putti with ostrich)

| Accession Nr.: | 20000 |

|---|---|

| Artist/Maker: |

Gubernatis, de, Pietro Paolo / cartoon by Raffaello Sanzio, Raffaello Santi (1483 - 1520) / designer |

| Manufacturer: | Barberini tapestry weaving manufactory (Rome) |

| Place of production: | Rome |

| Materials: | silk; wool |

|---|---|

| Techniques: | tapestry -weaving |

| Dimensions: |

height: 310 cm

width: 270 cm

sűrűség (felvető): 7 / cm

|

Made around 1635, the four so-called Medici tapestries in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts were commissioned by Pope Urban VIII, and are copies of a series of tapestries made more than a century earlier for Pope Leo X.

In the autumn of 1517, four years after Cardinal Giovanni di Lorenzo Medici—son of the famous, wealthy Florentine patrician, Lorenzo ‘il Magnifico’—was elected pope in Rome as Leo X, major works began in the Vatican’s papal apartments, the hall named after Constantine the Great. The imposing Sala di Costantino was the venue at the time not only for the papal audiences, but for the papal receptions as well, which were also splendid banquets. Raphael, the Prince of Painters from Urbino, who enjoyed the pope’s absolute confidence and who was overseeing the works, thus faced a special challenge. In addition to designing and executing the frescoes that depict the story of Constantine the Great, he also had to create special occasional decoration that would provide a fitting context for the culinary pleasures during the banquets. This purpose was served by twenty, identically sized tapestries, depicting putti at play, which were hung on moveable walls set up for the events.

In their choice of subject matter for the tapestries, Raphael and his client were moved by special notions that stemmed from classical antiquity. Putti were commonly considered at the time to be heavenly creatures that did not know fear, prejudice or suspicion, and these naked, winged children were widely used in the Italian art of the period, in a great many varieties. Their joyful, unselfconscious, impish games were supposed to be without the constraints of rationality and rules. They could be represented with the most diverse attributes and could be ‘invested’ with different symbolic, meaningful devices. The latter were also suitable for emphasizing the status of the client.

In designing the tapestries, Raphael had to take into account the ‘expectations’ that were voiced by the official papal propaganda after Leo X’s accession—ones that were more or less in harmony with what contemporaries anticipated and hoped for. Namely, that the reign of the new pope—the son of the highly respected Lorenzo il Magnifico, who had the backing of the fabulous wealth of the Medicis, a family of exceptional power and influence—would mark a flourishing new era, a veritable Golden Age in the history of Christianity and the Catholic Church. And since this new era, which had now dawned, was embodied in the person of the new pope himself, it was fitting and necessary that the meaningful symbolic devices that referred to him, his chosen name and papal motto, as well as to his family origins and attachments, should be given due emphasis.

There is no doubt that Raphael took all these considerations into account as best as possible. He made a point of suggesting and rendering the age of harmony and abundance, the new Golden Age hoped for and desired, through the use of purposeful and unmistakeable attributes, in conjunction with the symbols of papal power—the tiara, the sceptre and the keys—, the well-known emblems of the Medici family—the yoke and the ostrich feathers—and Leo X’s ’heraldic beast,’ the lion. The animals, mostly birds, that had symbolic meaning were also carefully chosen, including the ostrich, the peacock, the billy goat and the rabbit. Raphael gave his sketches to his student, Tommaso Vincidor, who, with the help of his collaborator, Giovanni da Udine, created the large cartoons from which the tapestries were woven in the best Brussels workshop of the time, under the direction of Pieter van Aelst.

The original series of tapestries arrived in Rome in 1524. By this time, however, both the originator of the compositions, Raphael, and the commissioner, Pope Leo X, had died. The original tapestries went missing around 1800, as they were probably destroyed during the Napoleonic Wars.

That we nonetheless have some knowledge of these particularly significant works of Renaissance textile art is mainly due to the fact that at the time of their creation, they elicited a lively contemporary response, with numerous pen-and-ink drawings and prints (copperplate engravings) made of them and their cartoons, alongside the descriptions (see here and here). Eugene Müntz was the first to reconstruct the twenty-piece series on the basis of the surviving textual and visual sources. (See Les tapisseries de Raphaël au Vatican et dans les principaux musées ou collections de l Europe. Paris 1897, 47–53; see here).

Between 1633 and 1635, copies were made of eight pieces from the series known as Gi[u]ochi di Putti (Games of the Putti), for Pope Urban VIII, presumably for his summer residence, the Palazzo del Quirinale. The copies were woven in Rome, in the Arazzeria Barberini, the manufactory founded around 1620 by the Pope’s nephew, Cardinal Francesco Barberini. The cartoons were made by Pietro Paolo de Gubernatis, after Raphael’s tapestries. Four of these newly made tapestries are now in the Museum of Applied Arts. Between 1637 and 1642, seven new tapestries were added to the series, designed by the court painter of Pope Urban VIII, Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, with putti now playing with the emblems of the Barberini pope (e.g. the beehive). Of this series, five tapestries have survived in the collection of the Palazzo Venezia, Rome (see here).

The first of the four tapestries in Budapest shows putti playing with an ostrich: one of them is plucking a feather from the bird’s tail to pin it into the laurel wreath on its head, which already holds two ostrich feathers. This is a reference to the Medicis: a diamond ring with three ostrich feathers was in the crest of Leo X’s grandfather, Piero de Medici. This armorial device appears in all the pieces of the series, in the frieze with the red base above the swastika-patterned border.

Emblems that refer to the Medicis and the patron, Pope Leo X, are also prominent in the second piece of the series: two putti play with Leo X’s device, a double yoke, while a third bends down to pick up the Medici emblem that lies on the ground, the red, blue and green ostrich feathers in a golden ring.

The third tapestry has Leo X’s chosen heraldic beast, a lion, in the centre. The king of the animal kingdom is pictured with a crown and an orb with the IHS Christogram on its head, while the putti around it hold the sceptre, the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, the papal tiara and the keys of St Peter.

In the fourth tapestry, the putti play with a rabbit, and above them, on a lush festoon of fruits and flowers, a peacock sits with its tail spread. Along with the praise of earthly pleasures, the unselfconscious frolicking of the putti also evokes other associations here: the peacock, with its magnificent plumage, certainly refers to vanity, and the rabbit to lechery and cowardice. The animals thus warn of the risks and dangers of abounding in pleasures, reminding the viewer of the need to tame desires.

The Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest purchased the four tapestries in 1948, from the former Hungarian ambassador to the Vatican, Elek Verseghi Nagy (1884–1967). They previously had been held in Paris, along with four other pieces, by Princess Mathilde Bonaparte. Following her death, the eight tapestries were put up for auction in May 1904, in the gallery of Georges Petit, a Parisian art dealer. Four of them were purchased by Count László Szapáry (1864–1939), who had them hung in his Budapest mansion. Shortly afterwards, the tapestries were acquired for the Viennese collection of Camillo Castiglioni (1879–1957), an Italian banker, who sold them in 1925 through the Amsterdam auction house Frederik Müller. Later they became the property of Bernheimer, a Berlin art dealership, before they were purchased, in the 1930s, by Elek Verseghi Nagy and his Dutch wife, Elisabeth Janssen (1900–1934), who placed them in their Röjtökmuzsaj palace.

In 1994, the New York Metropolitan Museum acquired two other pieces of the series from the art market. Another piece from the group appeared in 2002 in the New York gallery of Vojtech Blau, while the whereabouts of the eighth, which was once owned by Berlin art collector Victor Hahn, are unknown.

Literature

- Szerk.: Horváth Hilda, Szilágyi András: Remekművek az Iparművészeti Múzeum gyűjteményéből. (Kézirat). Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 2010. - Nr. 18. (Szilágyi András)

- Szerk.: Szilágyi András: Medici kárpitok. Puttók játékai. Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 2008.

- Szerk.: Pataki Judit: Az idő sodrában. Az Iparművészeti Múzeum gyűjteményeinek története. Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 2006. - Nr. 152. (László Emőke)

- Szerk.: Campbell Thomas P.: Tapestry in the Rensaissance. Art and Magnificence. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2002. - p. 255.

- Szerk.: Pataki Judit: Művészet és Mesterség. CD-ROM. Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 1999. - textil 4.

- Szerk.: Imorde Joseph: Tapisserie und Poesie. Gianfrancesco Romanellis 'Giochi di Putti' für Urban VIII. Barocke Inszenierung. Akten des internationalen Forschungscolloquiums an der Technischen Universitat Berlin, 1996. Imorde, Berlin, 1999. - 72-103. (Weddigen Tristan)

- Szerk.: Lovag Zsuzsa: Az Iparművészeti Múzeum. (kézirat). Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 1994. - Nr. 134-135.

- Szerk.: Péter Márta: Reneszánsz és manierizmus. Az európai iparművészet korszakai. Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 1988. - Nr. 39.

- László Emőke: Flamand és francia kárpitok Magyarországon. Corvina Kiadó, Budapest, 1980. - Nr. 41.

- Szerk.: Miklós Pál: Az Iparművészeti Múzeum gyűjteményei. Magyar Helikon, Budapest, 1979. - p. 301.

- Csernyánszky Mária: Medici kárpitok. Giuochi di putti. Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 1946.

- Gróf Szapáry László műkincseiből. Vasárnapi Ujság, 60. (1913), 30. sz.. 1913. - 585., 593-595.